Meetings and birthdays

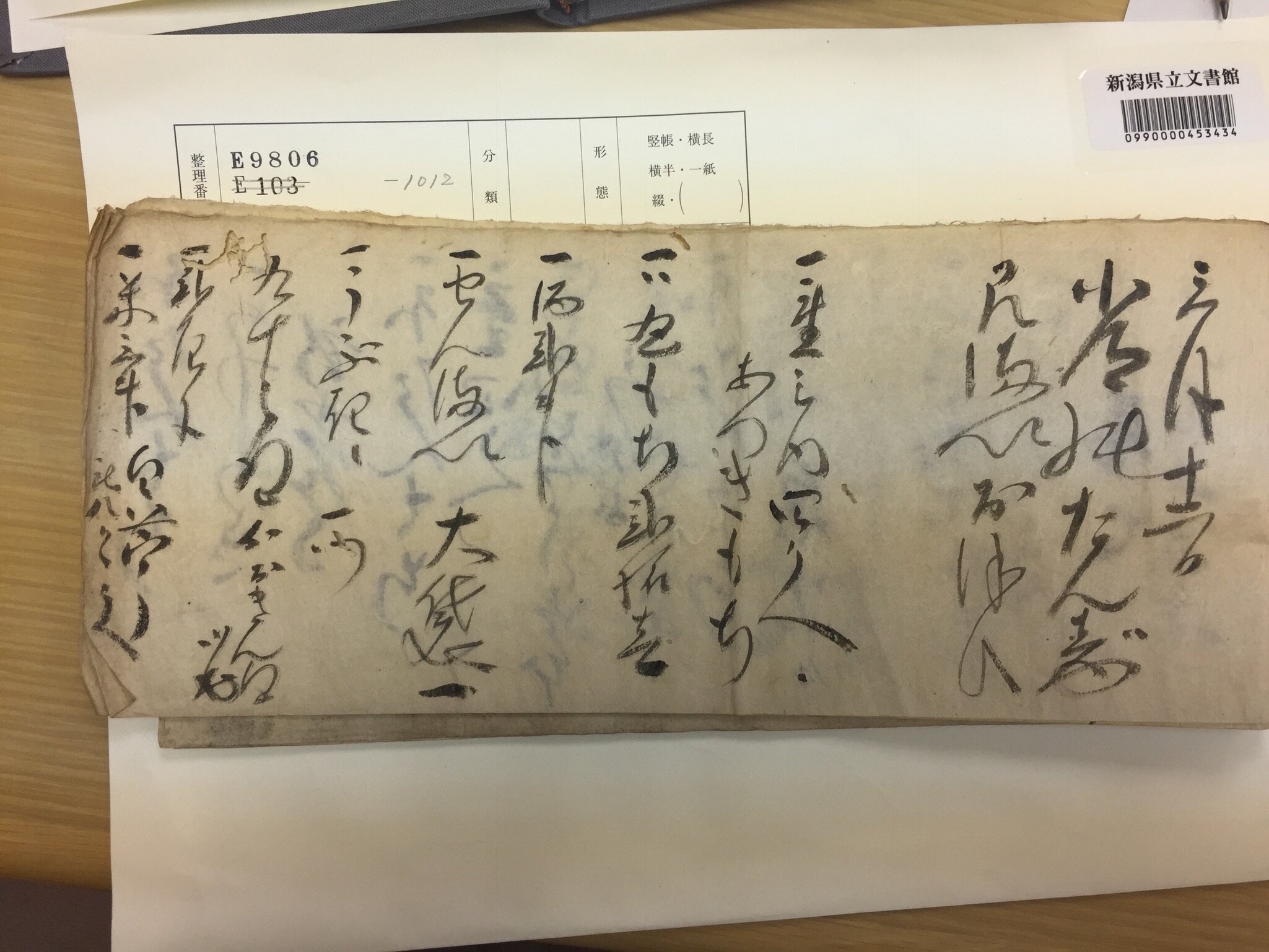

A record of Tsuneno’s birth, Rinsenji monjo #1012

I first encountered Tsuneno when I was a second-year assistant professor, desperate to find a document to assign in my Japanese history survey. I wanted them to read ordinary documents, the things of everyday life. Since not many of them were translated, I thought I’d do it myself.

Eventually, I landed on the website of the Niigata Prefectural Archives, which had an “online document-reading course” aimed at the local community. One of the featured documents was a letter from Tsuneno to her mother. If the archivists hadn’t transcribed it as part of the “document-reading course,” I never would have been able to read it. As it was, I still didn’t understand most of it. But some of the easier phrases jumped off the page. They seemed vivid, and almost shockingly contemporary. Tsuneno bragged about her wealthy boss and recommended a certain kind of hair oil. “Everything in Edo is delicious!” she wrote. She sounded exactly like me writing email home from my first trip to Tokyo. Even before I knew the rest of her story, I fell in love.

The archive provided a brief synopsis of Tsuneno’s life history - that she had been divorced and run away, and that there were dozens of letters about her in their collection. I flew to Japan as soon as I could. When I got to the archive, I spent days taking pictures of documents, even though it seemed futile. I could read nineteenth-century Japanese, but I couldn’t decipher the handwriting or understand the dialect in Tsuneno’s letters. They all looked like meaningless scribbles.

Even worse, I had the most terrible jet-lag I had ever experienced. I could barely stand up to take the photos. When I returned to Tokyo from the archive, I found out that it wasn’t jet-lag. I was pregnant.

Over the next few years, I had two babies: both boys, both beautiful and mostly happy, both of whom had chronic ear infections and regarded sleep as a mortal enemy. I was constantly exhausted, but Tsuneno didn’t let me go. I returned to the letters again and again, trying to teach myself to read her handwriting, sounding out every word. I traveled back to the archive almost every year and photographed more and more: her brothers’ letters, her father’s diary, village maps. I hired a Japanese research assistant and wore out a series of dictionaries devoted to the “destroyed style” of calligraphy. The spines broke and the pages scattered. There were water-radical characters in the diaper bag. There were person-radical characters under the sofa.

But I tried to read, and mostly failed. And then failed again. And then, suddenly, after a few days of doing something else, I’d come back to a document and realize it suddenly made sense. I wrote compulsively, sometimes on my phone, while rocking babies to sleep, or in the middle of chaotic birthday parties. I felt like I was being haunted by a stubborn, obsessive nineteenth-century ghost.

When I finally finished most of the first draft of Stranger in the Shogun’s City, I returned to the archive for a final fact check. I called up a document I had never seen, catalogued as the record of Tsuneno’s older brother’s birth. I flipped through, dutifully, and then stopped short. Hidden in the last pages, scribbled in what must have been Tsuneno’s mother’s or grandmother’s handwriting, was another account: “Third month, twelfth day: Tsuneno’s birth.”

I had to turn around and pretend to look at the reference books to avoid crying all over the page. It wasn’t just that I had never known the exact date of Tsuneno’s birth. It was also that – after nearly ten years – I could read it.

My disgusting, completely destroyed dictionary